Article By David Browne

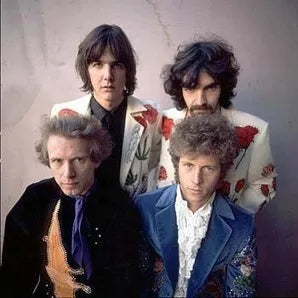

Photo of FLYING BURRITO BROTHERS – Credit: Jim McCrary/Redferns

The shows were over, but for Phil Kaufman, the headache was just beginning. Then the road manager for the Flying Burrito Brothers, one of the bands credited with finding the common ground between rock & roll and honky-tonk country, Kaufman had just returned home to Los Angeles, after some Burrito-related work in 1969. In the trunk of his Ford Country Squire station wagon were the embroidered cowboy suits the band had worn onstage and on the cover of its first album, The Gilded Place of Sin. Named after Nudie Cohn, the immigrant who owned the Hollywood store that made and sold the outfits, the Burritos’ “Nudie suits” were walking works of art, festooned with everything from poppy flowers to a smiling sun.

Before crashing for the night, Kaufman locked his car and trunk, where, he says, the suits were stashed in separate dry-cleaning bags. The next morning, to his horror, he saw that someone had broken into the wagon — one of the bags, containing bass player Chris Ethridge’s jacket and pants, was missing. “It was a really shitty neighborhood,” Kaufman says, “and they just grabbed something.”

In the decades since Ethridge’s suit mysteriously vanished, the ones belonging to Burrito Brothers Gram Parsons, Chris Hillman, and Sneaky Pete Kleinow remained in the possession of their families (Parsons died in 1973, Kleinow in 2007, and Ethridge in 2012). Last year, all three, encased in glass, became the centerpiece of Western Edge, an exhibit focused on California country-rock at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville. But Ethridge’s was considered a goner for good. Kaufman had filed a police report but with no results. The museum chased leads that led nowhere. “It was a whole series of dead ends,” says Mick Buck, curatorial director of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. “People who thought they might know, it turned out they didn’t know. Someone said it was destroyed. But nobody really knew. We had to abandon the idea of having the four suits together.”

In a sparkly twist on a rock reunion tour, Ethridge’s suit was finally returned to his family this year and, this week, will rejoin its three wool-gabardine brethren at Nashville’s Hall of Fame. But the journey of the outfit, from its owner to his estate, is also one of the strangest in the often shadowy world of rock memorabilia. At various points, the saga involves Elton John, Scotland, one of rock’s earliest and most profitable auctions, stressful legal wrangling, and a federal prosecutor who happens to be a fan of Emmylou Harris, Parsons’ duet partner. As Hillman says, bemusedly, “The Ethridge suit has a life of its own. I don’t know how that happened.”

MANUEL CUEVAS, NUDIE COHN’S CHIEF DESIGNER, remembers when the Burritos came around to Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors on Lankershim Boulevard in Hollywood. “Gram was fun,” recalls Cuevas. “He was the one who came around to me for so long. They say, ‘Well, we are planning to have a beautiful set of suits.’ It was a beautiful project.”

The Flying Burrito Brothers were far from the first musicians to don Nudie suits. Credited with launching the idea of the “Rhinestone Cowboy,” Kyiv-born tailor Cohn began making bejeweled jackets and pants for country stars like Lefty Frizzell and Roy Rogers. In the Fifties, Cohn was asked to make a gold lamé one for Elvis Presley; around the time the Burritos commissioned theirs, Michael Nesmith and Poco’s Richie Furay had Nudies, and the list would eventually include Sly Stone, Dollly Parton, ZZ Top, Jack White, and Beck. In a comeback few could have expected, Nudie suits — or facsimiles of them — have recently been worn by Lil Nas X and Post Malone, along with Wilco and Jenny Lewis.

The Flying Burrito Brothers never sold as many records as any of those artists. But the sight of its four members wearing individualized Nudie suits on the cover of The Gilded Palace of Sin itself an album that was ahead of its time, lent the outfits an air of subversive cool. The Nudie garb, says Wilco guitarist Patrick Sansone, “has a currency in pop culture and rock & roll culture because of that Burrito Brothers album cover. It’s such an iconic image. You see it referenced all the time, even by people who don’t really understand they’re referencing it. It’s a statement similar to the Beatles putting on the Sgt. Pepper suits.”

Parsons and Hillman formed the Burritos in the fall of 1968, after both men had parted ways with the Byrds, who helped instigate the fusion of country and rock with that year’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo. From the start, the men wanted Nudie suits; Parsons was a country fan and Hillman had seen them up close when his pre-Byrds bluegrass band shared bills with country acts. “You put that suit on and it meant something,” Hillman tells Rolling Stone. “It made you bigger than life. It took everything out of two dimensions and put them into three.”

Meeting with Cuevas, the musicians talked about designing their suits, and the Cohn team, including Cuevas, embroiderer Rose Clements, and tailor Jaime Castaneda, went to work. Each reflected the cosmic-cowboy sensibility of its owner. Hillman’s blue velvet one was decorated with a sun and Poseidon (both playing off his love of surfing) and peacocks (ever-present on his family ranch). Kleinow’s, a black velvet tunic, sported a pterodactyl on the front. Starting with its bell-bottom hip-hugger cut, Parsons’ had the most WTF-for-its-time design: a nude woman, marijuana leaves and poppies on the front, poppies on the back, and pills and cubes (the latter likely symbolizing acid) on the sleeves. “Gram’s was like a pharmacy,” Hillman cracks.

Ethridge’s was decorated with yellow and red roses — which, according to his daughter Necia, mirrored his love of the Hank Snow country classic “Yellow Roses.” “The rest of ours were goofy,” says Hillman. “But Chris’ was the most elegant suit. It smacked of the Old South.” The entire bill came to $2120, or about $500 per suit. Legend long had it that Parsons, who lived off a trust fund, paid for the clothing. In fact, according to Hillman, the band received an advance for signing with A&M and the funds were deposited into the group’s attorney’s trust account. Some of that money was then used to order and pay for the suits, with the bill going to the group’s lawyer.

The Burritos posed comfortably in the suits for the cover of The Gilded Place of Sin, but playing music onstage while wearing the outfits, made with the same material used in police and military uniforms, was a challenge. “Dad just said, ‘It was hot,’” says Necia Ethridge. “He said he felt kind of foolish. The times they were in, the clothes were trippy; people wore blue jeans. Nudie suits weren’t popular then.” Hillman recalls one disastrous night. “We did this one big promotional thing for A&M and wore the suits and it was almost like it was a jinx, because we didn’t play very well,” he recalls. “With the lights, the suits were glowing and you’re going, ‘Oh, my God.’”

On the road, the person in charge of the wardrobe was Kaufman, who came with his own wild backstory. Busted for weed smuggling in 1967, he was sent to prison in California, where he befriended a fellow inmate named Charles Manson. Ingratiating himself into the music business, Kaufman worked for the Rolling Stones and then the Burritos, acquiring the title “executive nanny.” Several years later, it would be Kaufman who infamously stole and burned Parsons’ body in the Joshua Tree desert after Parsons overdosed in a motel in 1973.

Kaufman says he was less than taken by the Burritos and their incongruous cowboy outfits. “I was new in the business and get these fucking guys with these silly suits that I had to look after,” says Kaufman. “We had to schlep them around. They looked good, but it was too soon to be in Nudie suits. If you show up at a hootenanny in fucking rhinestones, you’re gonna get a lot of hootin’. They looked like a freak show. But it was something Gram liked, so we had to do it.”

Ethridge, who died of pancreatic cancer in 2012, was the first of the original Burritos to leave, in the summer of 1969. Throughout his life, he instructed his family not to read anything written about him and the band, fearing they’d come across inaccurate info. During the last week of his life, however, Necia broached the subject of his departure. “I said, ‘What went on with the Burritos?’” she recalls. “He said some band members were not practicing as much as they should. And they would imbibe. Chris [Hillman] was definitely into practicing, but my dad felt they didn’t get to have that organic flow when you’re in a band. It was hard on him.” Seeing Parsons pull up in a limo while the other band members were jammed into a van didn’t help either.

After he broke with the Burritos, Ethridge went on to become a must-hire bassist in the L.A. music world, appearing on albums by Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt, John Prine, Judee Sill, Ry Cooder, Crosby and Nash, Randy Newman, and others. He also joined Nelson’s band. Necia Ethridge would sometimes ask her father about the missing suit. “He didn’t understand why his suit was taken,” she says. “He said, ‘I can’t understand. It kinda hurts my feelings.’” The Burritos themselves never wore the suits again after 1969; they disbanded in 1971.

By last September, everyone involved had pretty much given up on finding Ethridge’s Nudie. At the opening of the Country Music Hall of Fame’s Western Edge that month, CEO Kyle Young made what amounted to a public plea for anyone with knowledge of the stolen property to come forward. “Despite our best efforts, Chris Ethridge’s white suit with roses has vanished into the mists of history and is currently untraceable,” Young told the assembled crowd, which included Hillman, Cuevas, and Chris Isaak. “So, if you know someone who is proudly wearing it to local cookouts, let us know. We would love to borrow it.”

Little did anyone know that the suit had been hiding in almost plain sight for decades — and was about to be found again.

BORN A FEW YEARS AFTER THE SUIT vanished, Necia Ethridge grew up seeing photos of her father wearing it but never actually saw it. She too had gone in search of the suit, but came away empty-handed. Then, about two months after Young’s comments, Ethridge heard from an old friend of her fathers: The suit was in an auction in London.

Billed as “Elton John’s Nudie Cohn bespoke ‘Rocket Man’ suit, 1971,” the outfit was included in a sale on vintage fashion overseen by Kerry Taylor Auctions, a leading U.K. auction house. The writeup on the item noted that the name “Chris Ethridge” appeared inside the breast pocket and trousers on a label that Cuevas had included in each man’s suit. The lot also included the boots and cowboy hat that John wore with the jacket and pants.

The connection made no sense to Ethridge’s family and friends. But what few had known was that John had visited the Cohn store during his first American tour in late 1970. Like his songwriting partner Bernie Taupin, he was fascinated by America and the Old West (as would soon be heard on Tumbleweed Connection), and John bought a Nudie suit off the rack — it turned out to be Ethridge’s.

John was not available for comment, and Taupin says he recalls little about the origins of the suit. But in the first of several unlikely coincidences in the tale, Hillman’s future wife and manager, Connie Pappas Hillman, was executive vice president of John’s Rocket Record Company in the Seventies. She remembers the suit and believes no one involved had any idea it was stolen property. “Elton didn’t have a lot of money in 1970,” she says. “He ended up buying a suit off the rack, and that was the suit. It wasn’t unusual to buy something off the rack at Nudie’s. People would sell their clothes back if they weren’t going to wear the anymore. Elton knew who the Burritos were, but it seems to me that he didn’t make the connection that it was Chris Ethridge’s.”

Still, how the outfit traveled from the back of Kaufman’s station wagon to the front of Elton John’s closet remains the most baffling part of the story. Did the thief resell it to the Nudie store? Kaufman can’t understand it. “I don’t think anybody in Silver Lake ever heard of Nudie,” he says. “It was a hippie community. It’s a conundrum because I thought it was stolen and all of a sudden it shows up at Nudie’s and then with Elton John.” Necia Ethridge believes Kaufman’s story but still can’t grasp what happened: “It was a betrayal, not by a band member and not Phil Kaufman. It may have been someone close, but I don’t have any definitive proof.” Cohn himself died in 1984 and his store closed a decade later, although it eventually reopened as a mail-order business.

For a brief period, John went public with his new possession but no one realized it. In January 1971, he wore it on the British music show Top of the Pops during a performance of “Your Song.” Two months later, he donned the suit in his role as best man at Taupin’s wedding. The following year, John and his Ethridge duds were on the cover of the European single of “Rocket Man.” “It was 1972,” says Sansone. “If you were in the United States you couldn’t just open up a laptop and stream Top of the Pops. Nobody saw that stuff in the States for decades. The U.K. single of ‘Rocket Man,’ you’re not going to go into Tower Records and see that.”

The suit’s next hidden-in-sight exposure came in 1988, when John held a public auction at Sotheby’s. Amidst feather-boa costumes and bejeweled glasses, few seemed to take notice of the Nudie suit — save for an anonymous buyer in Scotland, a devoted Elton John fan who bought it for 4,000 British pounds (about $18,000 in today’s currency). When and if the new owner of John noticed the name “Chris Ethridge” inside one of the pockets, no one paid it any mind. The suit remained in the Scottish buyer’s possession until last year, when he decided to part with it. Kerry Taylor, who had worked at Sotheby’s on the original auction, now had her own business and, in another bit of serendipity, handled the resale.

For Necia Ethridge, who works as a mental-health counselor in Taos, New Mexico, the suit was more than just a remnant of her father’s past. After his death, she says the house in which he was living in Meridian, Mississippi (where he was born and raised) was burglarized, everything inside gone, and she was never able to retrieve any of it. “It was terrible,” she says. “So imagine now, years later, everything is gone, and there’s my father’s suit. I can’t even explain my feelings.”

When Ethridge reached out to Taylor about the suit and its backstory, Taylor admits she was caught off guard. “The whole thing was a bit of a nightmare, with Necia saying it was stolen,” says Taylor, who pulled the suit from auction while she investigated. The fact that Ethridge’s father’s name was inside was, Taylor says, “quite compelling”; Ethridge also had a bill of sale from the Nudie store. But Taylor needed more proof, namely a police report on the theft, and to Ethridge’s dismay, nothing turned up in the LAPD archives. Of her more recent conversations with the John camp, Taylor says, “All I can say is he acquired it properly and couldn’t remember the exact details.”

By chance, Wilco’s Sansone had been in the same Mississippi high-school art class as Necia Ethridge and the two became friends. Now, he suggested she get a lawyer. Wilco management connected her with Charles McKenna, a former federal prosecutor who handled insurance fraud, white-collar crimes, RICO violations, and similar cases and now works for the firm Riker Danzig. Although he normally doesn’t handle cases involving rock collectibles, McKenna was intrigued, in part because he was a fan of Emmylou Harris. McKenna sent what he calls “a stern, strong demand letter” to Taylor, making the case that U.S. law would apply because the outfit had been stolen in this country. “Our position was that under United States laws, we were entitled to that suit,” he says. “I don’t think [the current owner] committed a crime, but I don’t think he had good title to the property.”

With the possibility of litigation, Taylor says the situation grew stressful for the owner: “My client felt worried about the whole thing and wanted it to go away.” On February 10 — Chris Ethridge’s birthday — Taylor asked Ethridge to submit her best offer. It was accepted.

Everyone admits that the amount, which is undisclosed, is less than the lot would have brought on the market. “A lot of people would have recognized its significance as Elton’s earliest flamboyant outfit,” Taylor says. “But Necia made heartfelt pleas and my client is a nice man.” The day Etheridge had to fork over the cash turned out to be her own birthday. “So,” she says, “my birthday present to myself was buying a suit.”

A FEW MONTHS AGO, NECIA ETHRIDGE was finally reunited with her father — by way of his outrageous wardrobe. She and her family flew to London, where Taylor had the outfit displayed on a mannequin in a studio. In an almost comic final bit of delay, Ethridge and her daughters had to wait outside while Troy Paff, a filmmaker producing a documentary on the suit, dealt with audio issues. “I was like, ‘Don’t come in yet — go around the corner and have another coffee!’” Paff says. “They were buzzing with energy.”

Finally, Ethridge walked in. “The first thing I wanted to do was touch it,” she says. “I felt even like my dad was there in the room. It was kind of spiritual.”

As Ethridge and Paff saw for themselves, the outfit was in nearly perfect condition, save for a few tiny moth bites and a mysterious reddish stain on the pants. Ethridge wonders if it’s “a rum and Coke or a little bit of wine” from her father’s partying days. Hillman has a theory: “We were playing Steve Paul’s Scene in New York and I was helping Chris out the door when he consumed too much one night, and we had the suits on at the time.”

Back at her Airbnb in London, Ethridge draped the suit over her shoulder — “kind of like little hugs from my dad,” she says — and made preparations to fly it back to the States, carefully folding it into a carry-on bag. Once home, she reunited the suit with Cuevas, who immediately confirmed its authenticity. “There’s no way you can find anything like that in the world,” he says, “because every outfit was made individually.” Ethridge also allowed Sansone to try on the suit jacket. “It was a moment,” he says. “It fit me perfectly. I didn’t know they were that heavy.”

For many connected to the suit, its retrieval and museum display signal a form of belated redemption. Ethridge wants it to remind people of her father’s contributions to rock and country. “I wanted him to be acknowledged,” she says, “and this is my way to give him a bit of what I wish he had before he passed away.”

But to Kaufman, now 88, the idea that John and the unknown previous owner would pay thousands for the garb is baffling. “It’s a suit,” he says incredulously. “I’ve worked 50 years in the business and guitars are what people want.”

But when the suit makes its Country Music Hall of Fame debut today, Kaufman also sees the moment as a way of freeing himself from a different kind of prison. “That’s my albatross,” he says. “People were always saying, ‘Yeah, I think I saw it here,’ or ‘I saw it there.’ It’s been chasing me for years. I felt responsible for it. So, I’d like to hand it to her.”